Two centuries ago, UT was called East Tennessee College, but even in those days, its educational scope was much broader than the region it called home.

Samuel Carrick

Its founder, Samuel Carrick, had studied at Liberty Hall, the college in the Shenandoah Valley; despite the fact that it was later associated with a president named Robert E. Lee and renamed Washington and Lee, Liberty Hall in Carrick’s time was considered a hotbed of progressive thought, even abolitionism. A Presbyterian minister by the time he got to Knoxville—probably in 1790, just before the crude settlement was called Knoxville—Carrick began teaching almost as soon as he arrived, both within the church and without. One of his students was a younger Liberty College minister named Isaac Anderson, who in 1819 went on to found Maryville College.

David Sherman

Carrick’s successor was David Sherman, a Yale grad who had come to teach at a downtown prep school called Hampden-Sydney Academy. The school wasn’t associated with the Virginia university of the same name except by inspiration, but it was associated with UT’s forerunner and even helped East Tennessee College reopen in 1820 after an 11-year hiatus, under the leadership of Sherman, who saw an opportunity to galvanize a moribund college. The college and the prep school were formally associated for six years. The most durable boys’ prep school in Knoxville’s first century, Hampden-Sydney was still there 40 years later to play a similar role in helping our local college get back on its feet after the Civil War. Talk of a formal and permanent relationship never came to fruition—but perhaps inspired by the idea, the university supported a preparatory department. For a generation, high school students attended classes on the Hill.

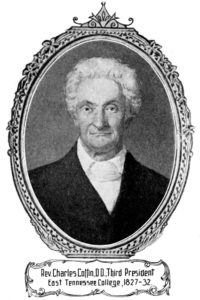

Charles Coffin

After Sherman quit in poor health, another Ivy Leaguer replaced him. Charles Coffin had attended Harvard and first came to Tennessee to lead the Greeneville college soon to be known as Tusculum.

Recruited to UT, he was in Knoxville for only five years, but Coffin was the scholar who shepherded the college to a higher elevation—on the Hill—and began the long tradition of teaching there.

Joseph Estabrook

Joseph Estabrook, from Lebanon, New Hampshire, was a Presbyterian who went to Princeton to train for the ministry. He left to become principal of Amherst Academy, which was associated with Amherst University. (Just a few years after his administration, an aspiring young poet named Emily Dickinson attended the school he had helped shape.)

Estabrook came to Knoxville not to teach at UT but first to be in charge of the Knoxville Female Academy, a respected institution for local women founded by Estabrook’s fellow New Englander Joseph Strong—whose name would resonate through UT history through descendants who attended over two centuries.

George Cooke

New Hampshire native George Cooke, a Dartmouth grad, came to lead the college in 1853. So most of UT’s leaders in the half-century after Carrick were alumni of the already-old Eastern colleges of what would only later become known as the Ivy League. The university evolved on the Hill with direct knowledge of the highest standards of education of the day.

Charles Dabney

Charles Dabney, one of UT’s longest and most influential leaders, earned his doctorate at the University of Gottingen in Germany.

Philander Claxton

Among the many progressive educators Dabney hired was Philander P. Claxton (1862–1957), who had also studied in Germany but didn’t have Ivy League roots. A Tennessee native, Claxton had earned two degrees from UT. He started his alma mater’s department of education, an achievement deserving of the honor of his name on a major building, but he was also an educator on a national scale as a US commissioner of education for 10 years, across three presidential administrations.

What is rarely remembered is that Claxton was the juggernaut behind an ambitious educational initiative that, in retrospect, is astonishing.

Its name, Summer School of the South, might strike modern ears as something less momentous than it was. Born in the Progressive era, it was a weekslong Chatauqua-style convention of public and private schoolteachers—especially from the South, but many came from other parts of the country—to hear groundbreaking lecturers from around the world. It was a festival of learning like nothing else at that time.

It launched in 1902, near the end of Dabney’s vigorous administration. Formally it had a separate board from the university’s, but it was held on the Hill, and the fact that Dabney, Claxton, and several other UT faculty members led it as organizers and lecturers makes it part of UT’s history. Some of the nation’s major scholars and reformers came to the summer school to give presentations. Educational philosopher John Dewey, then at Columbia, was a major attraction in 1904, rather early in his long and prolific career. In 1907, legendary Chicago reformer Jane Addams, founder of Hull House, was a featured lecturer. Other famous figures included William Jennings Bryan in 1911, when he was still a presidential hopeful (he would soon be Wilson’s secretary of state). Japanese author Toyokichi Iyenaga spoke about political science.

One notable former UT faculty member was among the visiting lecturers: classical scholar Ebenezer Alexander, who was by then known for his role, as US ambassador to Greece, in launching the international Olympic movement.

UT was a school with an enrollment of only 350, but Summer School of the South regularly drew more than 2,000 teachers who came to attend lectures or workshops on calculus, phonics, Euripedes, insect life, electricity, socialism, paper folding, botany, Kipling, music for children, architectural drawing, Dickens, and neurological anatomy—among dozens of other courses. At night, the same summer school presented performances by some of the world’s great musicians and actors, including Metropolita Opera baritone Giuseppi Campanari and internationally celebrated violinists Maud Powell and Albert Spalding. They performed the classics but also the work of modern living composers like Saint-Saens, Richard Strauss, and British composer Liza Lehmann.

The mix was exhilarating, like a Bonnaroo of knowledge and culture. And there had never been so many people on the Hill for any purpose.

There was live drama, too. Decades later, actor Charles Coburn would later be a familiar character actor in multiple Hollywood comedies, several of them directed by UT grad Clarence Brown, but early in the century he led the Coburn Players, a Shakespearean troupe that performed more than 100 times at about a dozen Summer Schools.

The Summer School survived and prevailed after the departure of President Dabney, hitting an all-time high attendance of over 2,500 in 1911. That was also the year that its organizer received his greatest honor, that of a post as US commissioner of education. Claxton moved to Washington, DC, and served with distinction as one of that high office’s more progressive and influential leaders. His Summer School, regarded as an annoyance by some later faculty—one president just didn’t like the looks of Jefferson Hall, the barnlike wooden shed where the larger lectures were held—continued, but became a more modest, pragmatic service with fewer big intellectual stars, resulting in a decline in enrollment.

One more Summer School was held in 1921, and some teachers conventions on campus in the 1930s drew comparisons to the old days. But the Summer School of the South became an idealistic memory. Historians suggest it jump-started summer sessions at a college that had previously just closed for the summer. And Claxton’s other creation, UT’s School of Education, has sent tens of thousands of teachers to thousands of schools around the nation.

UT is all about education, of course. But education doesn’t begin and end on this or any campus. It’s part of the nature of education that it spreads itself around.

UT has produced thousands of professors at other colleges and a few college presidents, including Ann M. Millner, recent president of Utah’s large Weber State University, which is now almost as large as UT; Edward Ayers, recent president of the University of Richmond; and Linwood H. Rose, recent president of James Madison University.

It’s interesting to consider whether the Summer School concept could be revived a century later. In some ways what Claxton pioneered is not that different from Hilton Head’s annual Renaissance Weekend, or the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland—or, on a much more modest scale, the Pecha Kucha slideshow presentation nights that have caught on in Knoxville and many other cities.

There’s still a lot to talk about. Maybe even more than there was in 1902.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

This story is part of the University of Tennessee’s 225th anniversary celebration. Volunteers light the way for others across Tennessee and throughout the world.

Learn more about UT’s 225th anniversary